Prologue.

At first in small groups, then in increasing number , armed men are crowding on the west bank of the Euphrates. There are infantrymen armed with spears, swords, javelins; there are elusive and proud horsemen, there are unerring archers. And also many carts and wagons, oxen and camels, donkeys and mules. The boats necessary to ferry all those men and those animals were set on fire by the enemy. How to switch to the other side?

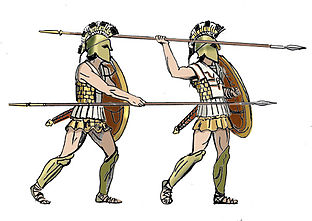

A group of men detaches from the main army. These men wear red cloaks, hold round shields, wield long spears. They speak Greek. They are hoplites, armoured infantrymen in the pay of the young prince who commands the army. They enter the water and head towards the opposite bank. Gradually, the others imitate their example. At first hesitant, then more and more invigorated, they go through those half-mile of still water, without getting wet above the chest. The Euphrates had never been forded in that way. Like the Red Sea in front of Moses, the big river has withdrawn its waters in front of the Cyrus the Younger’s army.

A sign of divine favour?

Darius and Parysatis had two sons ….

Generations of students have not forgotten the beginning of the Xenophon’s Anabasis: Δαρείου καὶ Παρυσάτιδος γίγνονται παῖδες δύο: Darius and Parysatis had two sons. The youngest was Cyrus, and according to Xenophon, he was an essence of nobility, magnanimity, bravery, loyalty, personified justice, and so on and so forth. Nobody else was worthy to be king, writes Xenophon. The latter was Artaxerxes (actually his real name was Arsaces) and the age was on his side: he was the firstborn and, for this reason, he was destined to succeed his father. The first one was his mother’s darling (Parysatis doted on him), the latter was studying as king (or ,better still, as the King of Kings) amid various court’s slanders and intrigues, sometimes with more than a reason. Like this one: pay attention, your brother is plotting against you. Word of Tissaphernes, a friend of Cyrus, and, therefore, for Arsaces, now appointed King with the name of Artaxerxes II, doubly credible. Fortunately for Cyrus, “mom” Parysatis remedies. Cyrus comes back unharmed to Sardis, and the matter ends there.

Or, rather, it begins there.

The march towards the interior.

By resorting to cunning tricks and taking good care not to reveal his true intentions if not to the most trustworthy among his, Cyrus enlists an army. He mostly wants Greek hoplites, the armoured infantry of those times. On the market there are a lot of them (the Peloponnesian War has just ended), ready to sell themselves to the highest bidder. Cyrus puts his hand in his pocket and soon he secures more than ten thousand of them with the tacit approval – it has been thought- of Sparta, whose most prominent general, Lysander, winner over the Athenians at Aegospotami (405 BC) thanks to the ships given him by Cyrus, felt tied by a debt of gratitude with the young prince.

Then Cyrus gives himself false enemies, now the Pisides, now Miletus, now the satrap Abrocoma, now Tissaphernes; he sends regularly the tribute to his brother, in order Artaxerses does not become suspicious; he leaves Sardis and marches towards the interior, entering regions with exotic names and many wonders; he receives a queen (Epiassa, Queen of Cilicia) with whom it seems that he have a love affair; he wades rivers, touches large and small cities, organizes military parades, rejoices when he sees his soldiers escaping to his heels in front of the Greek phalanx during a military exercise because in them he seems to see the soldiers of his Brother; he promises a pay raise to calm the protests and grumblings of his men, maybe wondering to himself where the proverbial contempt of the Spartans for the money went; he suffers the first casualties, he cools fights, he promises, punishes, condemns, forgives and rewards. And, parasang after parasang [1] , he gets closer to Babylon.

“All is lost but arms and valour.”

His brother – the King- for a while does not care. Would march against him one who is paying regularly the tribute? Then, he becomes suspicious, finally, with the help of Tissaphernes, he understands: the Pisides are a false problem : It’s me whom he wants. The mercenary soldiers of Cyrus have also a sneaking suspicion and more they advance inland, more their suspicion becomes certainty. The pacts were not these, the Greeks complain. The rumblings grow, thick words and in some cases, heavy stones fly; someone takes bags and leaves Cyrus. The whole charisma and the experience of the Spartan Clearchus – the commander of those men- and the gold of the aspirant King are needed to sort out the situation and to bring the Ten Thousand to Cunaxa and to the rendezvous with their destiny.

Bitter destiny, as we know. Artaxerxes had an exterminated army (Xenophon, exaggerating , tells about more than a million men; according to some modern historians they were around forty thousand), scythed chariots, archers, cavalry. It ‘s true: his army has been prepared in haste, his infantrymen are not Greek hoplites, not all of them wear the armour, they do not fight in a close ranks, but they are many, too many.

On the right wing of the Cyrus’ deployment however, the number seems to matter little: the Greeks anticipate the enemy, push themselves forward and break through. The pursuit begins, but, elsewhere some troubles start. Cyrus falls pierced by a javelin while, at the centre of the battle, is crossing his sword with his brother; the manoeuvre of encirclement conducted by Artaxerxes succeeds and the Cyrus’ Persian soldiers take flight. After the pursuit, the Greeks come back to the battlefield and they find it occupied by the enemy. They still do not know of Cyrus’s death . They know, however, they are into a deep trouble. And if they make fail an Artaxerxes’ attempt to wipe them out, they have got no illusions: until when can they withstand, without food, thousands of miles from home, surrounded by a hostile people and a hostile army?

At this point, a complex chess game begins. A chess game made of promises and threats, of hopes and shots of pride, of oaths and perjury, of double-dealings and lies, of underhanded behaviours and precarious truces, of surrender injunctions and indignant responses (“We keep the weapons: if you want them, come and take them”), of defections and night marches.

The king threatens havoc, but he seems to go easy with them, even if it is difficult to know the reason why (Is he satisfied to have done away with Cyrus? Is he afraid of the Ten Thousand? Does he not consider them a threat?). Among the Greeks there are differing views, opposing factions , little food, no boats to cross wide and deep rivers, fearful and uncertain allies (as Arieus). Only the weapons, the valour and the pride of one who has not been defeated remain. Not much, to be honest. The truces, therefore, are welcome and welcome are the open markets, where is it possible to buy food and welcome is the apparent no-hostility of the foe.

Mind you: they, the Ten Thousand, rather than to come back home, would willingly sell themselves. And – you can bet- even for much less than the dàric and half by which Cyrus paid them. But Arieus refuses their services and Artaxerxes can not let things ride. What figure would he do if he upheld in his service those who had tried to take the throne from him? How would his many subjects look upon his restless? As a sign of weakness, of course. And if, in future, did someone try again?

In this stage, Clearchus and Tissaphernes lead the dances. The first is a soldier who has a sterling character , the latter is a smart schemer; the first has bartered his own death sentence imposed in Sparta with another death sentence when he agreed to drive these officially non-existent ten thousand, the latter has turned flag when the wind has changed, leaving Cyrus for Artaxerxes; the first knows how to command and how to impose the discipline by the word and by iron hand, the latter brags of never made deeds, bragging, for instance, of having killed Cyrus on the battlefield and attracting over himself the wrath of the terrible Parysatis ,who a few years later will make kidnap and behead him; the first, hoarse voice and grim face, goes straight to the chase, the latter says and does not say, alludes and hides; the first knows how to fight and does not avoid the danger, the latter, at Cunaxa, advises his soldiers to stay away from the Greek hoplites; the first shows uncommon military skills, the latter a devilish skills to make appear white as black and vice versa; the first, a soldier among soldiers, leads his hoplites on their way back, the latter, looming presence, follows them from afar.

It is in force a truce, the King has pledged to let them go, Tissaphernes should escort them. But it is an ambiguous and perpetually suspended matter, ready to fall for a nothing. Tissaphernes disappears and reappears, he is silent for days before making hear himself again, he reassures and promises, he hints and threats, he makes around rumours of impending attacks, he keeps on tenterhooks the retreating Greeks and he pulls from his the undecided Arieus. There is urgency to unlock the situation, to clarify once and for all, and then come what may.

Arrived at the river Zapata( or Zab), Clearchus looks for a talk and gets it: he explains his point of view, defends his good faith, attributes the Tissaphernes’ unfriendly and suspicious attitude to scattered artfully slanders. The satrap reciprocates with honey words and proposes: come to me together with other strategists and commanders of the regiment: I will reveal to you the slanderers’ names. Keep alert , do not trust in him , many say to him. But Clearchus agrees to take the risk. And he ends beheaded and with him his colleagues Proxenus, Menon, Socrates and Sofenetus.

The Ten Thousand’s epic begins on this moment.

Anatomy of a commander.

Xenophon , even if he is not the commander in chief ( he is the commander of rear-guard), however, is the soul of katabasis, the “March to the Sea”, of the Ten Thousand. He suggests, encourages, empowers, sets in example. He says: we must not fear the enemies: they have violated the terms of the agreement , offending the Gods. Nor we can deal with them: they have betrayed once, they will betray again. And then, have you forgotten your history? Are you or not the descendants of those who have already defeated the Persians at Marathon and Salamis? Let’s name new commanders, therefore, and let us take off quickly from here. And let us get free of all superfluous to travel more shipped. Carts and tents do not serve us, they slow down our march. Rivers? There is no river that can not be forded. The enemy knights? Have you ever seen anyone, in battle, dying for a bite of a horse? The knights are men like us and, in some respects, in combat they are also more vulnerable than us. The food? Till now we havepaid it (salty), from now on we will take it. The Gods? Will they support those who have dishonoured them, betraying the commitments? And when a loud sneeze of a present -considered a favourable omen – emphasizes the latter statement, Xenophon takes advantage immediately of it: “What have I told you? The Gods are with us. ”

Nor Xenophon restricts himself to exhortations. He, who is not a soldier, leads a department to conquer the summit of a hill, not hesitating to dismount if this is reproached as a privilege by those who are sweating and trudging under the weight of the shield; he, who is not a soldier , organizes the march order of the expedition, fielding the hoplites squarely to protect the luggage and the main army; he, who is not a soldier , creates a unit of slingers of Rhodes to counter the deadly shooting of enemy slingers or organizes small units of cavalry.

Woe, indeed, to lower the guard. Tissaphernes has no intention to slacken his hold: he teases, harasses, sends out his men to test the reactions of the enemy; he flexes his muscles, he strikes from afar with the slingers and archers, he avoids like the plague a close contact with the deadly spears of the hoplites; he applies the scorched earth policy, forcing the Ten Thousand to head north, towards the mountains. And, when he encamps, he does so at considerable distance from the enemy to avoid unpleasant surprises during the night.

In this game cat and mouse, the Greeks learn from their own mistakes. They learn to make more flexible the structure of the square of the hoplites, for instance, too much crowded when it moves in tight spaces and too large when it moves in the wide spaces. Or to create mobile units of peltasts (lightly armed infantrymen) able to intervene in times of need or to make some sorties. But, as far as they learn, they can not do miracles. Following the outward road is impossible; on the new road, the eastern bank of the Tigris is manned by the Tissaphernes’ men . Remain the passes of the mountains. But the Ten Thousand must hurry, to prevent that the foe make snapping the trap. Those mountains, beyond which lies the “great and prosperous “Armenia’ are the undisputed reign of the Carduchians. Today we call them Kurds.

To hell and back.

The Carduchians hate the King of Kings, but even more they hate to have foreigners around their country. Especially armed foreigners . So when they see those men with red cloaks climbing on the trails of their mountains, they do not even want to know who they are or what intentions they have: they disappear in a flash and prepare to ambush. The Ten Thousand know little of them , except that they resent the Persian yoke. For this, they do not expect a friendly behaviour on their part, but they hope at least an attitude of non-belligerence. Moreover, they have no other choice: Tissaphernes is pretty darn close this time. And he is willing to get serious. And so, entered the Carduchians’ territory, at first the Ten Thousand go easy: they march at night, save the villages, are freed of redundant to walk faster, leave alone the women. And they hope to get away.

Vain hope. The seven days spent in the Kurdish territory are for Xenophon and C. a real nightmare. The Carduchians do not give them respite. They rains boulders on them, they penetrate shields and armours by arrows of the size of a javelin, they occupy the hills, guard the passes. Every little progress is paid in blood, every pass is severely disputed, behind a conquered high ground, lies another high ground which has to be conquered. By comparison, the clashes with the Tissaphernes’ army had been insignificant skirmishes.

But the worst is yet to come. Released at last from hell and came in sight of the river Kentrites, the Ten Thousand find their way barred by a vast army, deployed on the banks of the river and the surrounding heights, while behind them the Carduchians crowd out increasingly threatening from the mountains. A stroke of luck – the accidental discovery of a convenient stepping- a manoeuvre carried out in a masterly way by Cheirosophus and Xenophon -and why not ?- the favour of the Gods allow them to reach the other shore, to rout the enemy and to leave the Carduchians behind them. Before the attack, the equally effective shouts of incitement of the prostitutes in tow were mixed to the solemn and holy paean.

The Western Armenia is ruled by the satrap Tiribazus. He is a king’s friend, he helps him to mount on horseback (honour , this one, given only to few) and, as Tissaphernes, whose he appears a copy, he does not practise what he preaches , he offers a truce and prepares ambushes . According to Xenophon, at least. The season, then, does not help: it often snows , it’s cold, the feet swell, one risks the frostbite. The glare of the snow blinds, the hunger is felt, the wind does not let up, the pitfalls multiply. Many soldiers fall to the ground without any apparent reason, they come again to life when one gives them something to eat. More than bulimia as some claim, theirs seems raging hunger. Others, arrived near a hot spring, refuse to continue to advance; one tries to protect the weaker ones, including the prostitutes in tow, but who can not carry on is left to his fate. Behind the Ten Thousand, there are some groups of enemies looking for loot: they take possession of the delayed pack animals ,they grab weapons and objects left on the ground.

The pitfalls hatched by Tiribazus, however, fail : the Ten Thousand almost always anticipate him, occupying the high grounds and taking control of the crossings. Or, if we see the issue with different eyes from those of Xenophon, we could say that the truce holds.

But there are many hostile peoples around (the Chalybians, the Taochians, the Fasianians) who are oblivious of the truce and firmly decided to stand in the way those foreigners. They will fail, of course, and we could not address it at the bottom if it were not for a curious episode on which it is worth dwelling.

An ancient evil?

So: the Taochians are garrisoning a mountain pass. Not a pass whatever, but “the pass”, the one that opens the doors of the plain. What to do? Let’s do this, Xenophon proposes, more and more increasingly put into the shoes of strategos: we pretend to attack on one side and we bring , instead, the main blow on another part. Chances of success? Many, assuming you have men who, not seen, are capable of conquering the peak by a sudden attack while the main force is implementing the diversionary tactic. And who has the quickest hands than the Spartans, accustomed as they are, even from early childhood, to steal without getting caught? They do not consider the theft a guilt, but being caught with their hands in the bag. Yes, says Xenophon, from this point of view, the Spartans are well educated: we entrust to them the mission and I am sure, they will put into practice the received teachings and they won’t get surprised .

Look who is talking! is the reply. An Athenian, namely a master in stealing the public money. In Athens, more one steals , more he is authoritative, bigger is the thief and higher is the public office he occupies. Beautiful stuff! The voice is that one of the Spartan Cheirisophus, the words are those ones of Xenophon. Taking advantage of the occasion, he , pro-Spartan and with a grudge against his fellow citizens, takes off a few pebbles from his shoes. Are the Spartans thieves ? Sure, but they are chicken thieves, when we compare them to the thieves of the public money.

Thalatta! Thalatta!

The Ten Thousand, after having crossed the pass and after having arrived in the plain without having resolved the question whether are more thieves the Spartans or the Athenians, are expected by other obstacles and by other hostile populations. To get food – the problem is always that one – it is necessary to storm the “fortresses”, i.e. the fortified villages, situated along the way. Many of these villages resist and in one of them Xenophon is witness of a spectacle, according to him, “tremendous” (deinòn): before the Greeks enter the conquered village, the women throw their children down from the walls and then follow them, imitated also by many men. Why that mass suicide? Why that Masada at few steps from the Black Sea?

Xenophon writes: it has been a tremendous and scary spectacle. But it adds nothing else about it. Why does not he do? Do those women and men take their own lives and the lives of their children because the Ten Thousand were preceded by a bad reputation? Because they burned, looted and raped? Likely, even if little or nothing about the violence against women filters out from the account of Xenophon. War is not only courage, bravery, valour, contempt of danger, heroism, how the Anabasis’ author wants to make believe to us: war is also – if not above- blood, violence, killings, abjection. Any war. Even that one of Xenophon, despite Xenophon. Could so many men, hunted, attacked, desperate, running out of food, abstain from the violence? Could they not consider women as spoils of war? Could they abstain from committing all kinds of violence? Difficult, perhaps impossible.

What should one say , for instance, about the guide given to the Greeks by a local governor in order he see them to the sea? Does he do it out of liking or because he wants to use them? Because does he admire their courage, or because does he want , through them, to strike terror into his enemies? And , strangely enough, just in enemy territory, the guide encourages them to plunder and ravage the region. Xenophon writes: then we realized the true intentions of the governor: not for liking he was helping us, but to use us for his own benefit. But he does not say if the remains of the Ten Thousand follow the guide’s exhortations or if they refuse, if they devastate or if they refrain from doing so. Such explanations do not give immortality.

Immortality lives of other sensations, it feeds on other events. On the summit of Mount Techeis an unusual move is noticed , excited shouts are heard , more and more intense. Another attack by those to whom have been burned houses and crops stolen? Fearing the worst, Xenophon spurs his horse, summons his men, rides to the summit. The shout is getting higher, it passes from mouth to mouth, it explodes into an exclamation that clears months and months of toil, danger, hunger, cold, starvation: Thalatta! Thalatta! The sea! The sea!

They did it. Whom should they thank? Their determination and bravery? Artaxerxes, who could have wiped them out at any time and has not done? The Gods?

But that is not a time of questions: that is the moment of the emotion , the moment of return to life. The men cry and hug each other: on the shores of that sea (today Black Sea) for eight thousand and six hundred of them, the Katabasis is over.

What happened next, from Trebizond to Constantinople, belongs to another story.

Epilogue.

In the ‘Anabasis, Xenophon celebrates above all himself and his own ideas, but also he celebrates the courage and determination of a handful of determined men ; he does not tell about a lot; he does not say enough about the miseries of war; implicitly he considers the looting and violence if not a merit, surely a necessity; he provides valuable geographical, historical, military, political information about the wide Artaxerxes II’s empire. Who knows how to read lines can find useful information: the difficulties are overcome if one remains united; the Persian Empire is a paper tiger; marching straight to the heart of that empire is not impossible. But to achieve the enterprise, knowledge alone is not enough: it is needed a dream. The dream only can make feasible the impossible, only the dream, “infinite shadow of the truth”, can move the mountains.

And the dream forms itself in the mind and in the heart of a young king, attentive reader of the ‘Anabasis. In the company of Xenophon, the dream of that young king runs along the valleys of Mesopotamia, crosses the mountains, passes over deserts, goes beyond Babylon, beyond Susa until drawing up the boundaries of the world.

That dream is the dream of a young king grew up in a rough and difficult country, educated in the myth of Achilles, taught by Aristotle. That dream is the dream of a young king named Alexander.

Alexander, son of Philip. Alexander the Great.

Suggested reading:

Andrea Frediani, Le grandi battaglie dell’antica Grecia , Newton Compton, 2005

Andrea Frediani, the greatest battles of ancient Greece, Newton Compton, 2005

Valerio Massimo Manfredi, L’armata perduta , Mondadori, 2007

Valerio Massimo Manfredi, The lost army, Mondadori, 2007

Senofonte, Anabasi di Ciro , Libri I-IV, traduzione di Franco Ferrari, introduzione di Italo Calvino, Bur, 1989

Xenophon, Anabasis of Cyrus, Books I-IV, translated by Franco Ferrari, introduction by Italo Calvino, Bur, 1989

On this site, if you like, you can also read:

The Days of the earth and the water. Marathon 490 BC: a bare handful of hoplites against the mightiest army in the world at that time.

Read the article.

The Hare and the mare. On the eve of Thermopylae, the God’s notices to the King of Kings ….

Read the article.

The Greek forces at the disposal of Cyrus:

4,000 hoplites under the command of Senias;

1,500 hoplites and 500 light infantrymen (peltasts) under the command of Proxenus;

1,000 hoplites under the command of Sofenetus of Stymphalus;

500 hoplites under the command of Socrates the Achaean;

300 hoplites and 300 peltasts under the command of Pasion of Megara;

1,000 hoplites, 800 Thracian peltasts, 200 Cretan archers and, subsequently, about 2,000 men of the troops of Senias and Pasion (who meditated desertion, and indeed, once in Syria, will desert) under the command of the Spartan Clearchus.

1,000 hoplites, 500 peltasts under the command of Menon;

1,000 hoplites under the command of Sofenetus of Arcadia;

300 hoplites under the command of the Syracusan Sosides;

700 Spartan hoplites under the command of Cheirisophus;

400 Greek deserters from the army of the satrap Abrocoma.

Moreover, Cyrus could count on a fleet of 35 ships under the command of the Spartan Pythagoras and 25 ships under the command of the Egyptian Tamos. According to the ‘Anabasis, the Ten Thousand had a tactical support of 100,000 Persian soldiers under the command of Arieus (modern historians write of twenty thousand soldiers) and twenty chariots armed with scythes.

The Artaxerxes II’s forces according to Xenophon:

900,000 men (the satrap Abrocoma with another 300,000 people will come to Cunassa five days after the battle);

6,000 horsemen;

150 scythed chariots.

[1] The parasang was a linear measure corresponding roughly to about 5,300 meters. According to Xenophon, Cyrus and C. walked more than five hundred of them (535 to be exact) fromSardis to Cunaxa.

This is an automatic translation from Italian. Excuse the mistakes.